Genealogy Day 2025 is on Saturday, March 8, 2025: Genealogy

Saturday, March 8, 2025 is Genealogy Day 2025.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

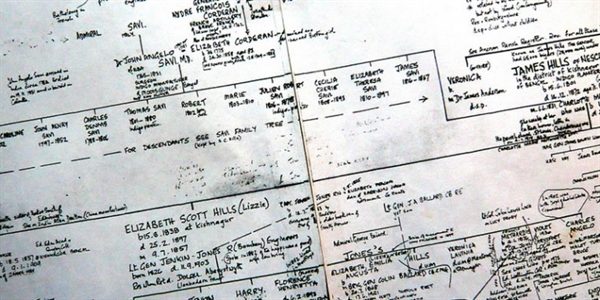

Genealogy, or study regarding genealogy, is among the quickest growing hobbies today. Using the creation of today's technology, for example computer systems and also the internet, trying to find records of the forefathers is becoming a lot more accessible.Established in 1997 included in Celebrate Your Title Week, Genealogy Day was produced to inspire a pursuit on one’s genealogy.Activities you can take part in for Genealogy Day vary from an easy family tree, that is a great activity for kids, to beginning your personal research for any bigger project. An excellent beginning point for genealogy is meeting with family and family buddies, and making notes, then going after that. You will be amazed how rapidly things can begin to fall under place. If you wish to try a task with children, draw a tree and also have them write what they are called of the family to the hands or legs leaving, together with pictures.

Tyler :-

Recorded in the spellings of Tyler, Tiler and Tylor, this interesting surname is of Anglo-Saxon and French origins. It was originally an occupational surname for a maker or layer of tiles. The derivation is either from the Olde English pre 7th Century word "tigele", itself from the Latin "tegula", meaning to cover or from an early French form introduced into English by the Normans after the Conquest of 1066, and derived from the words "tieuleor or tuilier". It would seem that the first recording of the name (see below) is from this source, but it has not survived as a modern surname. Tiles were used for floors and pavements during the Middle Ages, and were not used for roofing to any great extent until the 16th Century. The surname development includes: Robert le Tiler (1222, Essex); Geoffrey le Tylere (1279, Huntingdonshire); and Simon le Tyeler of Norfolk in 1286, whilst Wat Tyler was the leader of the Peasants Revolt in England in 1381. John Tyler (1790 - 1862) was the tenth president of the United States of America in 1841. The first recorded spelling of the family name is shown to be that of Roger le Tuiler, which was dated 1185, in records of the Knight Templars in the 12th Century. This was during the reign of King Henry 11, known as "The Builder of Churches", 1154 - 1189.

English :-

This interesting surname derives from the Olde English pre 7th Century "Englisc" meaning "English" and was originally given as a distinguishing name to an Angle as distinct from a Saxon. Both the Angles and Saxons were West German people who invaded England in the 5th and 6th Centuries A.D.. The Scottish form "Inglis" denotes an Englishman as opposed to a Scottish borderer whilst the form "English" referred to an Englishman living in Strathclyde. In the Welsh border counties the name would be given to an Englishman in a preponderatingly Welsh community. It may have been commonly used in the early Middle-Ages as a distinguishing epithet for an Anglo-Saxon in an area where the cultures were not predominantly English, for example in the Danelaw area, Scotland and parts of Wales, or as a distinguishing name after 1066 for a non-Norman in the regions of most intensive Norman settlement. However, at the present day the surname is fairly evenly distributed throughout the country. In the modern idiom, the name is found as Inglish, Inglis and English. On July 3rd 1560, Friswide English married Thomas Sheppard, at St. Mary Magdalene, Bermondsey, London, and William, son of Alexander English, was christened on September 7th 1567, at the same place. The first recorded spelling of the family name is shown to be that of Gillebertus Anglicus which was dated 1171, in the "Pipe Rolls of Herefordshire", during the reign of King Henry 11, known as "The Builder of Churches", 1154 - 1189.

Missing Genealogy?

Maggie,

People overcome this every day; however, the thing to remember is that there are no shortcuts. What you need to do is get all of the knowledge you have of the family together first. Start with your husband. Collect birthdates, birth places, marriage information, death dates, and death places. Once you have collected all applicable information on your husband, move back to his parents, then his grandparents. Once you have collected the dates, interview all of the living relatives. You will be astounded how much information is out there. For instance, my great grandfather was a twin. We heard this information from my dads brother; however, my dad and his five other siblings didn't have this information. Write down all the stories that you hear, even if you think that they aren't true. Usually, folklore is dabbled with little pieces of truth.

It is likely that there are vital records at least as far back as your husbands grandparents, maybe even his great grandparents depending on how old they are and how many years are between generation. If you collect the ones you can and try to validate them with burial records and obituaries, you may find some of the suprises that are now apparently well hidden. When you get back before 1930, census records can aid you in your search. The thing to remember is that peoples names aren't always spelled right in the census either. It will likely require some hunting and pecking.

Keep in mind that many people claim that their name changed when they came to America, but usually if there was a change, it was likely in the spelling. I have found with my Dutch ancestors many simply Americanized their names, the meaning stayed the same. For Example, Veldhuis became Fieldhouse, Ostenbrug became Estenbridge, etc. brug is the dutch word for bridge, Veld is the Dutch word for Field, and huis is the Dutch word for house. Usually, a name change can be explained this way or by something similar. Very few actually changed their name just to change it or changed it to escape persecution. People have generally been proud of their names over the course of history.

So, the answer is there just is simply no shortcuts or any websites to get this information from. The answer is trace your husbands line back, person by person, generation by generation and the answers will present themselves to you.

Genealogy and Foucault!?

In most cases Foucault’s reference to genealogy has nothing to do with the study of ones ancestors, like the following passage:

The genealogy of knowledge consists of two separate bodies of knowledge: First, the dissenting opinions and theories that did not become the established and widely recognized and, second, the local beliefs and understandings (think of what nurses know about medicine that does not achieve power and general recognition). The genealogy is concerned with bringing these two knowledges, and their struggles to pass themselves on to others, out into the light of the day.

Genealogy does not claim to be more true than institutionalized knowledge, but merely to be the missing part of the puzzle. It works by isolating the central components of some current day political mechanism (such as maintaining the power structure which diagnoses mental illness) and then traces it back to its historical roots (Dreyfus and Rabinow, p.119). These historical roots are visible to us only through the two separate bodies of genealogical knowledge described above.

Foucault says, "Let us give the term 'genealogy' to the union of erudite knowledge and local memories which allows us to establish a historical knowledge of struggles and to make use of this knowledge tactically today (Genealogy and social Criticism, p.42)."

The genealogical side of analysis tries to grasp the power of constituting a domain of objects. If a society were to institute the role of medicine man, for example, and give him special privileges, we would thereby "constitute the object of medicine man." Until we established and institutionalized this practice, nothing could be called a "medicine man." The genealogy explores what was not evident because of the institutionalization of knowledge by those in power.

(See Discourse on Language which is the appendix in the Archaeology of Knowledge.); Whereas archaeologystudies the practices of language (in a strict sense), genealogy uncovers the creation of objects through institutional practices (Dreyfus & Rabinow, p.104). Whereas the archeological historian claims to write from a neutral, disinterested perspective, the Nietzschean or Foucaultian genealogist admits the political and polemical interests motivating the writing of the history (Hoy, 1986, p.6-7).`

For a richer account of this concept click here to read a brief paraphrase of the first chapter of Foucault's The Archaeology of Knowledge

Here appears a fundamental principle for introducing Foucault’s power. He uses the genealogy precisely because it rejects the claim that truth can be found by the exposition of historical sequences. Put simply, change happens due to a conflict occurring nowhere. There is no truth inherent in the study of historical developments; the phrase itself would likely be contested by Foucault. Does this mean that the genealogy pays little attention to the details of beginnings and ends in history? “On the contrary, it will cultivate the details and accidents that accompany every beginning; it will be scrupulously attentive…[the genealogist] must be able to recognize the events of history, its jolts, its surprises, its unsteady victories and unpalatable defeats” (144). The genealogist does not ignore historical sequences but instead declines to give them authority to dictate truths on cause and effect. So of what use is this information on the genealogy in this investigation of Foucault’s power? To begin with, it is a reminder of one element that makes Foucault accessible: the common topical content of his genealogies. Further, the use of genealogy introduces Foucault’s thoughts on truth and knowledge. By showing that truth does not conform to an origin and that historical investigation does not inevitably lead to primary truth he reminds the reader of the following:

"In appearance, or rather, according to the mask it bears, historical consciousness is neutral, devoid of passions, and committed solely to truth. But if it examines itself and if, more generally, it interrogates the various forms of scientific consciousnesses in its history, it finds that all these forms and transformations are aspects of the will to knowledge: instinct, passion, the inquisitor’s devotion, cruel subtlety, and malice" (162).

This insight, that even historical inquiry that purports to be objective is subject to other elemental processes such as the will to knowledge, alerts the reader that what is at stake in this power inquiry is more than just cause and effect, dominance and slavery.