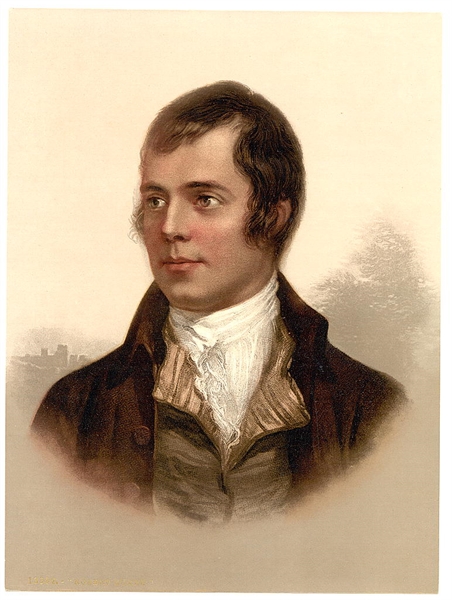

Robert Burns Day 2025 is on Saturday, January 25, 2025: can anyone tell me what the poem "to a louse" by robert burns means?

Saturday, January 25, 2025 is Robert Burns Day 2025.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

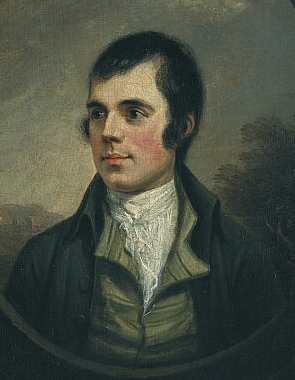

Analysis of Robert Burns

In Robert Burns’ poem “To A Louse”, he describes how he was sitting in church behind a woman that had a bug crawling around in her hair and around the ribbons in her hat. This entire poem entails how he feels about the bug crawling on this woman that he’s been watching and he also jokes about the whole situation about how the bug should be on someone dirty rather that on the apparently unsuspecting woman.

In the first stanza, Burns first notices the bug crawling on the woman. He asks himself (and the bug) where it’s going. He also says that the bug has probably been in the woman’s hat or hair for quite some time because his reaction is the same as seeing the bug for the first time on her. He also says that the bug has probably been well taken care with this woman, but I now in sear

. . .

The downside about the bug being present on the woman is because in that day in age, personal hygiene wasn’t as big of a deal as it is in present times; only for those of the higher class.

In the second stanza, Burns is upset that this bug has decided to dwell with this woman that he has described as “such a fine lady.

In the last stanza, Burns thinks that the woman should be given the gift of seeing herself as people see her and it would save her from embarrassment and give her some kind of insight. She could be the old woman that he was describing, or the mother of the poor boy.

However in the seventh stanza, Burns takes it upon himself to tell the woman sitting in front of him about the bug. He says that he wouldn’t have been surprised if he had spotted the bug on some old woman’s flannel hat or underneath the clothes of a poor boy. This could be why the bug is roaming around. Burns probably felt that a woman, such as the one being the part of the object of this poem, looked too pleasant to have this invader travel all over her and feed off of her. Or that God should allow us to see ourselves as others see us. He tells her not to make too much movement to draw attention to herself. ” In the conversation with himself, he tells the bug to find someplace else to roam such as on someone that is poor.

In conclusion, Robert Burns’ poem “To A Louse” is a humorous poem that has some satire in it. This could be why Burns is questioning the bug’s reason for being around the woman.

What inspired the poet Robert Burns to write "Tam O' Shanter"?

It was a local story. The poem first appeared in the Edinburgh Magazine for March 1791, a month before it appeared in the second volume of Francis Grose's Antiquities of Scotland, for which it was written. Robert Riddell introduced Burns to Grose. According to Gilbert Burns, the poet asked the antiquarian to include a drawing of Alloway Kirk when he came to Ayrshire, and Grose agreed, as long as Burns would give him something to print with it.

Burns wrote to Grose in June 1790, giving him three witch stories associated with Alloway Kirk, two of which he said were 'authentic,' the third, 'though equally true, being not so well identified as the two former with regard to the scene'. The second of the stories was, in fact, 'Tam o' Shanter'. This is Burns's prose sketch of it to Grose:

'On a market-day, in the town of Ayr, a farmer from Carrick, and consequently whose way lay by the very gate of Alloway kirk-yard, in order to cross the River Doon, at the old bridge, which is almost two or three hundred yards farther on than the said old gate, had been detained by his business till by the time he reached Alloway it was the wizard hour, between night and morning.

Though he was terrified with a blaze streaming from the kirk, yet as it is a well known fact, that to turn back on these occasions is running by far the greatest risk of mischief, he prudently advanced on his road. When he had reached the gate of the kirk-yard, he was surprised and entertained, thorough the ribs and arches of an old gothic window which still faces the highway, to see a dance of witches merrily footing it round their old sooty black-guard master, who was keeping them all alive with the power of his bagpipe. The farmer stopping his horse to observe them a little, could plainly desern the faces of many old women of his acquaintance and neighbourhood. How the gentleman was dressed, tradition does not say; but the ladies were all in their smocks; and one of them happening unluckily to have a smock which was considerably too short to answer all the purpose of that piece of dress, our farmer was so tickled that he involuntarily burst out, with a loud laugh, 'Weel luppen, Maggy wi' the short sark!' and recollecting himself, instantly spurred his horse to the top of his speed. I need not mention the universally known fact, that no diabolical power can pursue you beyond the middle of a running stream. Lucky it was for the poor farmer that the river Doon was so near, for notwithstanding the speed of his horse, which was a good one, against he reached the middle of the arch of the bridge and consequently the middle of the stream, the pursuing, vengeful hags were so close at his heels, that one of them actually sprung to seize him: but it was too late; nothing was on her side of the stream but the horse's tail, which immediately gave way to her infernal grip, as if blasted by a stroke of lightning; but the farmer was beyond her reach. However, the unsightly, tailless condition of the vigorous steed was to the last hours of the noble creature's life, an awful warning to the Carrick farmers, not to stay too late in Ayr markets.'

i need to argue robert burns is the greatest scot...?

some hae meat and cannot eat

and some hae meat that want it

but we hae meat and we can eat

and so the lord we thank it

On turning her up in her nest, with the plough, November, 1785

We again see how, in the words of Thomas Carlyl, the poet "rises to the high, stoops to the low, and is brother and playmate to all nature." This is, by readers gentle and readers simple, acknowledged to be one of the most perfect little gems that ever human genius produced. One of its couplets has passed into a proverb:- "The best laid schemes o' Mice an' Men, gang aft agley."

Listen to this in Real Audio

With thanks to Marilyn Wright and

the Flag in the Wind

Surely one of the finest poems written by Burns, containing some of the most famous and memorable lines ever written by a poet, yet, to this day not really understood by the mass of English-speaking poetry lovers, for no other reason than that the dialect causes it to be read as though in a foreign language. All readers of Burns know of the "Wee sleekit cow'rin tim'rous beastie" but not many understand the sadness and despair contained within the lines of this poem. What was the Bard saying when he was inspired by turning up a fieldmouse in her nest one day while out ploughing? - George Wilkie

Wee, sleeket, cowran, tim'rous beastie,

O, what panic's in thy breastie!

Thou need na start awa sae hasty,

Wi' bickering brattle!

I wad be laith to rin an' chase thee,

Wi' murd'ring pattle!

I'm truly sorry Man's dominion

Has broken Nature's social union,

An' justifies that ill opinion,

Which makes thee startle,

At me, thy poor, earth-born companion,

An' fellow-mortal!

I doubt na, whyles, but thou may thieve;

What then? poor beastie, thou maun live!

A daimen-icker in a thrave 'S a sma' request:

I'll get a blessin wi' the lave,

An' never miss't!

Thy wee-bit housie, too, in ruin!

It's silly wa's the win's are strewin!

An' naething, now, to big a new ane,

O' foggage green!

An' bleak December's winds ensuin,

Baith snell an' keen!

Thou saw the fields laid bare an' wast,

An' weary Winter comin fast,

An' cozie here, beneath the blast,

Thou thought to dwell,

Till crash! the cruel coulter past

Out thro' thy cell.

That wee-bit heap o' leaves an' stibble,

Has cost thee monie a weary nibble!

Now thou's turn'd out, for a' thy trouble,

But house or hald.

To thole the Winter's sleety dribble,

An' cranreuch cauld!

But Mousie, thou are no thy-lane,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best laid schemes o' Mice an' Men,

Gang aft agley,

An' lea'e us nought but grief an' pain,

For promis'd joy!

Still, thou art blest, compar'd wi' me!

The present only toucheth thee:

But Och! I backward cast my e'e,

On prospects drear!

An' forward, tho' I canna see,

I guess an' fear!